The Importance of 2D Representations in the Lives of Young Children

An excerpt from my upcoming book Young Architects at Play (Redleaf Press, 2020)

As digital technology advances, our relationship with maps — as learners and as navigators of the physical world — has changed. Today we use global positioning systems (GPS) and digital assistants like Siri and Alexa to help us get from place to place. Gone are the days when we carried accordions of paper road maps in our cars and asked strangers for directions on street corners.

Children who are learning to navigate their world still need experiences with paper maps for many of the same reasons that children who are learning to read still need books on paper. Children need tangible, physical, sensory experiences to learn and to understand new ideas with depth and complexity.

An architectural structure, whether a child’s simple block tower or a complex Manhattan skyscraper, is a solid. In terms of geometry, it exists in a three-dimensional space. A drawing or blueprint on a piece of paper, in contrast, exists in a two-dimensional space, or, as described in Euclidean geometry, on a plane or flat surface.

When children move from working in 3D, such as creating solid structures with blocks or cardboard, to working in 2D, such as drawing a picture or creating a blueprint of their structure with paper and pencil, they are using different tools and different motor skills. They are also using different cognitive skills and expanding their thinking in new ways. When we are challenged to represent a 3D structure in 2D, our minds must interpret and imagine the shapes and architecture of our design in new ways. The same is true when children are invited to draw a blueprint or design first, and then build the structure shown in their drawing. Moving from 3D to 2D, as well as from 2D to 3D, both involve an exciting cognitive process that sparks deep learning and creativity.

Learning that involves creating multiple representations of an idea or object is at the heart of the Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education. Reggio-inspired educators call this concept “the hundred languages of children.” As mentioned in the introduction to this book, Loris Malaguzzi, one of the founders of the infant-toddler centres and preschools of Reggio Emilia, famously wrote, “The child has a hundred languages, a hundred thoughts, a hundred ways of thinking, of playing, of speaking.” Malaguzzi recognized that when children are invited to explore and represent their ideas in new ways, using new tools and new methods, with each new representation they will notice something different and learn to pay attention to the beautiful and interesting details in their world.

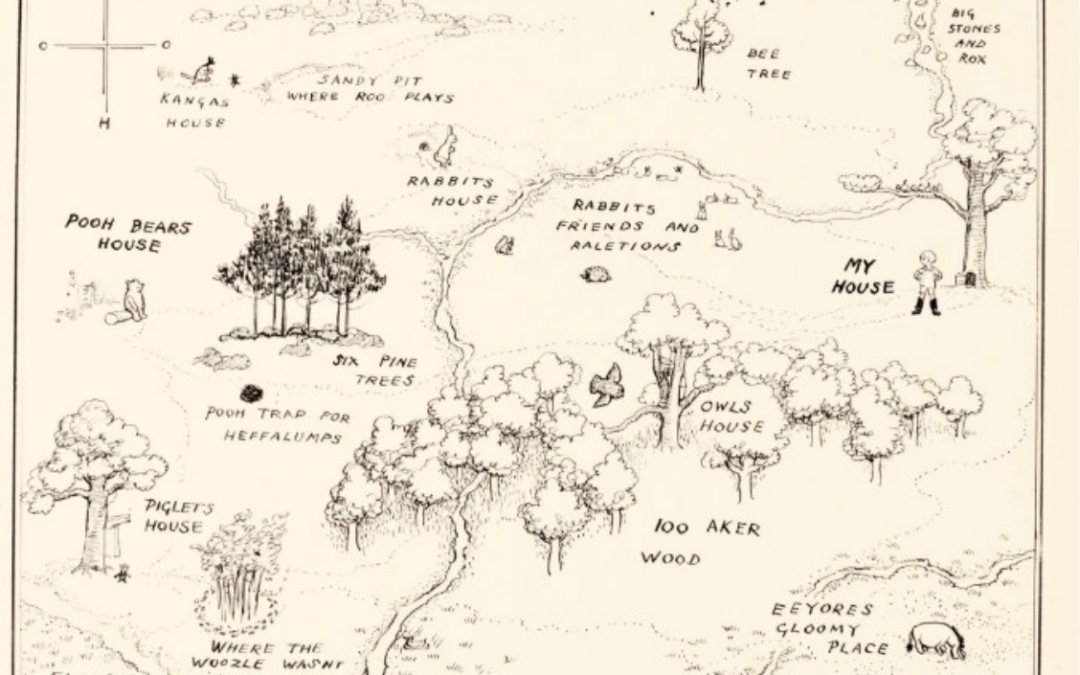

Personally, I am drawn to the aesthetic beauty of maps and blueprints. As a child, my favorite books were those that included an illustrated map of the story’s setting at the beginning of the book. I was particularly enchanted by E.H. Shephard’s illustrated map of the Hundred Acre Wood in the opening pages of A.A. Milne’s Winne the Pooh. Another favorite was Jules Feiffer’s map of the Kingdom of Wisdom found on the endpapers of The Phantom Tollbooth. Blueprints, floorplans, and illustrations of architectural structures offer a similar aesthetic as maps in their geometric order, often including beautiful patterns and symmetry. Simply providing children with a quality children’s atlas, such Aleksandra Mizielinska and Daniel Mizielinski’s beautiful Maps (Big Picture Press, 2013), will likely spark some inventive drawing and interesting classroom conversations.

I’ve frequently observed that when children are given graph paper (paper printed with a grid of fine lines) instead of plain drawing paper, they will often choose to draw buildings, patterns, lines, and symmetrical designs that are either intentionally created as a map or will resemble a map. Often the difference between a drawing and a map is simply one of perspective. An essential characteristic of maps and floorplans the perspective from a “bird’s eye view.” We are viewing what is represented on the page as if we are looking at it from above. This change in perspective can be challenging for young children to grasp, but we can scaffold their learning process by providing provocations and experiences that expose them to maps and the meaningful role of maps in their world.

Teachers can set up a workspace in their classroom, either permanent or temporary, for making maps and blueprints. In addition to a children’s atlas and examples of different kinds of maps or globes, provide children with a variety of tools that will inspire children to draw maps or blueprints. Include graph paper in various sizes and textures, sharpened pencils, fine-tip markers, rulers, and tracing tools. A set of rubber stamps can be used to create icons or landmarks on maps and blueprints. The benefits of these activities are significant. When children learn about maps and blueprints they are developing important spatial reasoning skills. They are also learning math concepts related to measurement and scale.

There’s no harm in exposing children to the use of digital tools and artificial intelligence for navigation, but children will learn with more autonomy and creativity if their use of these virtual maps are balanced with their experience creating and using physical and tangible objects. In the example described above in which a child talks about where her mommy works, the teacher can help the child create a simple map on paper that shows just two landmarks: home and mommy’s workplace. The child can draw a line between the two points to represent the streets her mommy takes to drive to work. The child could be invited to add another landmark – her preschool – and draw additional lines of connection. The child’s active role in connecting these locations on paper will not only support her cognitive development but will likely also support her social and emotional development as well. Then, after the child has been deeply engaged in creating her own map, the teacher could invite the child to compare her map to an actual paper map or to a digital map on a phone, tablet, or computer screen. The teacher can ask the child questions that promote critical thinking about maps and technology, such as “How is your map different from the map on the computer? How is it the same? Which map do you like better? Why?”

Recent Comments